The party guests who arrived on the evening of June 23, 2022, at the Tudor-style mansion on the coast of Maine were a special group in a special place enjoying a special time. The attendees included some two dozen federal and state judges — a gathering that required U.S. marshals with earpieces to stand watch while a Coast Guard boat idled in a nearby cove.

Caterers served guests Pol Roger reserve, Winston Churchill’s favorite Champagne, a fitting choice for a group of conservative legal luminaries who had much to celebrate. The Supreme Court’s most recent term had delivered a series of huge victories with the possibility of a crowning one still to come. The decadeslong campaign to overturn Roe v. Wade, which a leaked draft opinion had said was “egregiously wrong from the start,” could come to fruition within days, if not hours.

Over dinner courses paired with wines chosen by the former food and beverage director of the Trump International Hotel in Washington, D.C., the 70 or so attendees jockeyed for a word with the man who had done as much as anyone to make this moment possible: their host, Leonard Leo.

Short and thick-bodied, dressed in a bespoke suit and round, owlish glasses, Leo looked like a character from an Agatha Christie mystery. Unlike the judges in attendance, Leo had never served a day on the bench. Unlike the other lawyers, he had never argued a case in court. He had never held elected office or run a law school. On paper, he was less important than almost all of his guests.

If Americans had heard of Leo at all, it was for his role in building the conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court. He drew up the lists of potential justices that Donald Trump released during the 2016 campaign. He advised Trump on the nominations of Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Before that, he’d helped pick or confirm the court’s three other conservative justices — Clarence Thomas, John Roberts and Samuel Alito. But the guests who gathered that night under a tent in Leo’s backyard included key players in a less-understood effort, one aimed at transforming the entire judiciary.

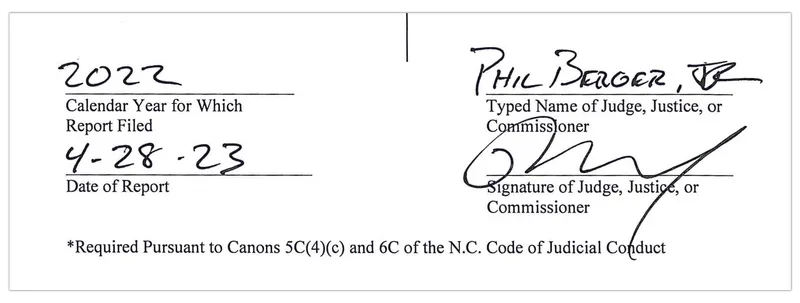

Many could thank Leo for their advancement. Thomas Hardiman of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals had ruled to loosen gun laws and overturn Obamacare’s birth-control mandate. Leo had put Hardiman on Trump’s Supreme Court shortlist and helped confirm him to two earlier judgeships. Kyle Duncan and Cory Wilson, both on the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, both fiercely anti-abortion, were members of the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, the network of conservative and libertarian lawyers that Leo had built into a political juggernaut. As was Florida federal Judge Wendy Berger, who would uphold that state’s “Don’t Say Gay” law. Within a year of the party, another attendee, Republican North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Phil Berger Jr. (no relation), would write the opinion reinstating a controversial state law requiring voter identification. (Duncan, Wilson, Berger and Berger Jr. did not comment. Hardiman did not comment beyond confirming he attended the party.)

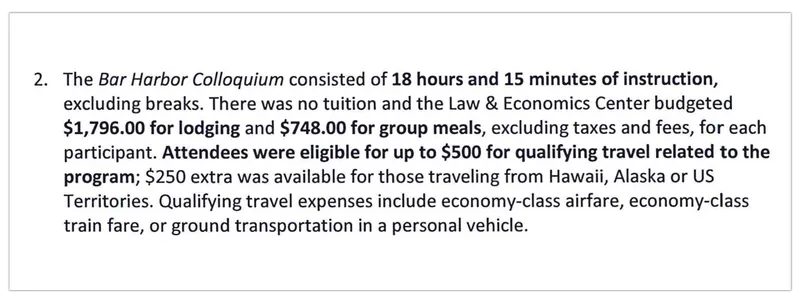

The judges were in Maine for a weeklong, all-expenses-paid conference hosted by George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, a hub for steeping young lawyers, judges and state attorneys general in a free-market, anti-regulation agenda. The leaders of the law school were at the party, and they also were indebted to Leo. He had secured the Scalia family’s blessing and brokered $30 million in donations to rename the school. It is home to the C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State, named after the George H.W. Bush White House counsel who died this May. Gray was at Leo’s party, too. (A spokesperson for GMU confirmed the details of the week’s events.)

The judges and the security detail, the law school leadership and the legal theorists — all of this was a vivid display not only of Leo’s power but of his vision. Decades ago, he’d realized it was not enough to have a majority of Supreme Court justices. To undo landmark rulings like Roe, his movement would need to make sure the court heard the right cases brought by the right people and heard by the right lower court judges.

Leo began building a machine to do just that. He didn’t just cultivate friendships with conservative Supreme Court justices, arranging private jet trips, joining them on vacation, brokering speaking engagements. He also drew on his network of contacts to place Federalist Society protégés in clerkships, judgeships and jobs in the White House and across the federal government. He personally called state attorneys general to recommend hires for positions he presciently understood were key, like solicitors general, the unsung litigators who represent states before the U.S. Supreme Court. In states that elect jurists, groups close to him spent millions of dollars to place his allies on the bench. In states that appoint top judges, he maneuvered to play a role in their selection.

It was not enough to have a majority of Supreme Court justices. They needed to see the right cases brought by the right people and heard by the right lower court judges.

And he was capable of playing bare-knuckled politics. He once privately lobbied a Republican governor’s office to reject a potential judicial pick and, if the governor defied him, threatened “fury from the conservative base, the likes of which you and the Governor have never seen.”

To pay for all this, Leo became one of the most prolific fundraisers in American politics. Between 2014 and 2020, tax records show, groups in his orbit raised more than $600 million. His donors include hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer, Texas real estate magnate Harlan Crow and the Koch family.

Leo grasped the stakes of these seemingly obscure races and appointments long before liberals and Democrats did. “The left, even though we are somewhat court worshippers, never understood the potency of the courts as a political machine. On the right, they did,” said Caroline Fredrickson, a visiting professor at Georgetown Law and a former president of the American Constitution Society, the left’s answer to the Federalist Society. “As much as I hate to say it, you’ve got to really admire what they achieved.” Belatedly, Leo’s opposition has galvanized, joining conservatives in an arms race that shows no sign of slowing down.

Historians and legal experts who have watched Leo’s ascent struggle to name a comparable figure in American jurisprudence. “I can’t think of anybody who played a role the way he has,” said Richard Friedman, a law professor and historian at the University of Michigan.

To trace the arc of Leo’s ascent, from his formative years through the execution of his long-range strategy to his plans for the future, ProPublica drew on interviews with more than 100 people who know Leo, worked with him, got funding from him or studied his rise. Many insisted on anonymity for fear of alienating allies or losing access to funders close to Leo. This article also draws on thousands of pages of court documents, tax filings, emails and other records.

“I can’t think of anybody who played a role the way he has.”

After months of discussions, Leo agreed to be interviewed on the condition that ProPublica not ask questions about his financial activities or relationships with Supreme Court justices. We declined and instead sent a detailed list of questions as well as facts we planned to report. Leo’s responses are included in this story.

Having reshaped the courts, Leo now has grander ambitions. Today, he sees a nation plagued with ills: “wokism” in education, “one-sided” journalism, and ideas like environmental, social and governance, or ESG, policies sweeping corporate America. A member of the Roman Catholic Church, he intends to wage a broader cultural war against a “progressive Ku Klux Klan” and “vile and immoral current-day barbarians, secularists and bigots” who demonize people of faith and move society further from its “natural order.”

Leo has the money to match his vision. In 2021, an obscure Chicago businessman put Leo in charge of a newly formed $1.6 billion trust — the single-largest known political advocacy donation in U.S. history at the time. With those funds, Leo wants to expand the Federalist Society model beyond the law to culture and politics.

The guests at Leo’s party in June 2022 celebrated into the night. One esteemed attendee imbibed so much he needed help to get up a set of stairs. Eventually, the guests boarded buses back to their hotel. The next morning, the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization news broke: The Supreme Court had overturned the constitutional right to an abortion. When Leo next stepped out for his regular walk, it was into a world he had remade.

When Leo was in kindergarten, he got in a fight over Matchbox cars. “There was a classmate who had a nasty habit of punching me in the nose on the playground,” Leo wrote in response to a question about his earliest memories of growing up Catholic. “I gave him one of my Matchbox cars, hoping a little kindness would help. He accepted the gift and punched me again anyway. I saw then that doing what our faith requires isn’t always going to make life easier or more comfortable, but you have to do it anyway.”

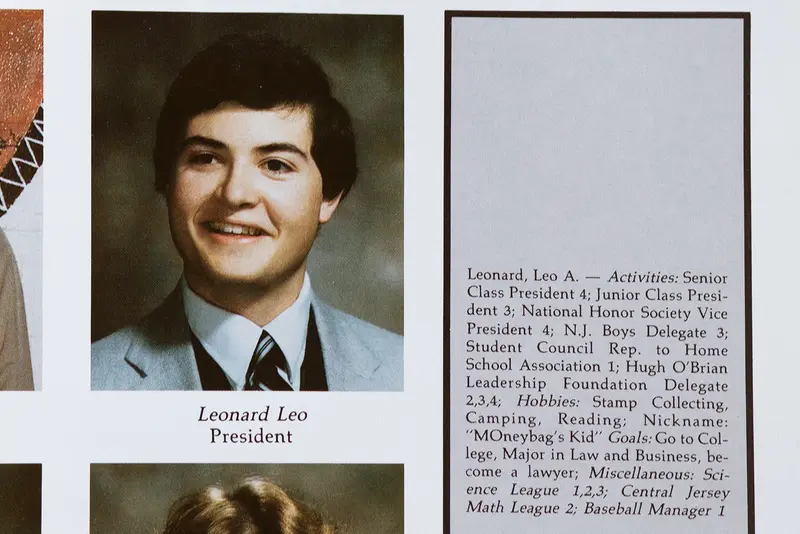

Leo was born on Long Island in 1965. When he was a toddler, his father, a pastry chef, died. His mother remarried and the family eventually settled in Monroe Township, a central New Jersey exurb where you’re not sure if you root for the Yankees or the Phillies.

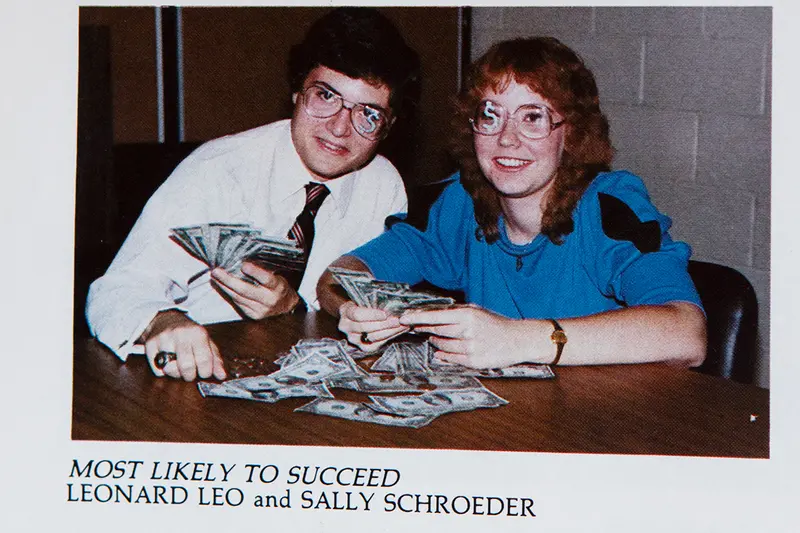

In the 1983 yearbook for Monroe Township High School, Leo, who often dressed in a shirt and tie, was named “Most Likely to Succeed.” He shared the distinction with a classmate named Sally Schroeder, his future wife. In the yearbook photo, they sit next to each other holding bills in their hands, with dollar signs decorating their glasses. Leo told ProPublica that he was so effective at raising money for his senior prom and class trip that his classmates nicknamed him “Moneybags Kid.”

When Leo arrived at Cornell University as an undergraduate in the fall of 1983, a counterrevolution in the legal world was gaining momentum. Iconoclastic scholars led by Yale University’s Robert Bork and the University of Chicago’s Antonin Scalia were building the case for a novel legal doctrine known as originalism. When interpreting the Constitution, they argued, judges and scholars should rely solely on the “original intent” of the framers or the “original public meaning” of the document’s words when they were written. Originalism was a rebuke to the idea of a “living Constitution” and the more expansive approach taken by the liberal Supreme Court majority under Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Law students were also fueling this new movement: In the spring of 1982, three of them founded the Federalist Society, a debating and networking group for conservatives and libertarians who felt ostracized on their campuses. Scalia and Bork spoke at the group’s first conference, at Yale Law School. There weren’t enough people to fill the school’s auditorium, so they held it in a classroom.

Leo encountered the Federalist Society while working as an intern for the Senate Judiciary Committee in Washington in the fall of 1985. At a luncheon hosted by the group, Leo heard a speech that he later said “had an enormous impact on my thinking.” It was delivered by Ed Meese, Reagan’s new attorney general. Meese made an impassioned declaration that originalism would be the guiding philosophy for the Reagan administration. “There is danger,” Meese said, “in seeing the Constitution as an empty vessel into which each generation may pour its passion and prejudice.”

Leo continued to Cornell Law School. The Federalist Society had no presence on campus, so Leo founded a chapter in the fall of 1986. He brought Meese and other conservative scholars to give talks. This went largely unnoticed by Leo’s classmates. To be a conservative legal thinker in those days was to be dismissed as a fringe type. Originalism “wasn’t something that I personally took very seriously,” said Mike Black, a classmate of Leo’s at Cornell Law. “I was clearly wrong.”

If his early brushes with the Federalist Society shaped Leo’s legal philosophy, then the battle over Robert Bork’s Supreme Court nomination in the fall of 1987 showed him how rancorous judicial fights could be. The attacks on Bork’s views were “character assassination,” Leo would later say, fueling a sense of grievance that liberals and the mainstream media demeaned conservatives. But it was also a failure on the part of the Reagan White House, which hadn’t anticipated the fierce opposition to Bork and was unprepared to defend him.

Leo and his new wife, Sally, moved to Washington after Leo finished law school so he could clerk for two federal judges. Then he had a choice: Take a job with a firm, or work full time for the fledgling Federalist Society.

Leo chose the Federalist Society. But first, he took a short leave to work on what would turn into one of the most contentious Supreme Court nominations in modern history. The nominee was an appeals court judge named Clarence Thomas who Leo had befriended during a clerkship. Leo was only 25 years old. Allegations of sexual harassment by law professor and former Thomas adviser Anita Hill had surprised Thomas and his supporters, and the George H.W. Bush White House scrambled to discredit her. Leo was tasked with research. He spent long hours in a windowless room gathering evidence to bolster Thomas. The Senate confirmed him 52 to 48, the narrowest tally in a century.

The searing experience of the Thomas nomination was soon followed by another shock.

In a 5-4 decision in 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey to uphold the constitutional right to an abortion. The three justices who wrote the majority’s opinion — Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor and David Souter — were all Republican appointees. Here was the greatest challenge to the movement: Even an ostensibly conservative nominee could disappoint. So Leo and his allies set out to solve this recurring problem. They needed to cultivate nominees who would not only start out loyal to the cause but remain stalwart through all countervailing mainstream pressures. Leo and his allies concluded that they needed to identify candidates while they were young and nurture them throughout their careers. What they needed was a pipeline.

That meant finding young, talented minds when they were still in law school, advancing their careers, supporting them after setbacks and insulating them from ideological drift. “You wanted Leonard on your side because he did have influence if you wanted to become a Supreme Court clerk or an appellate clerk,” said one conservative thinker who has worked with Leo. “He was very good at making it in people’s interests to be cooperating with him. I don’t know if he did arm-twisting exactly. It was implicit, I would say.”

The strategy was a hit with donors. As Leo took on more responsibilities as the group’s de facto chief fundraiser, the Federalist Society’s budget quadrupled during the ’90s, with industry executives and major foundations making large donations. The Federalist Society did not respond to a detailed list of questions.

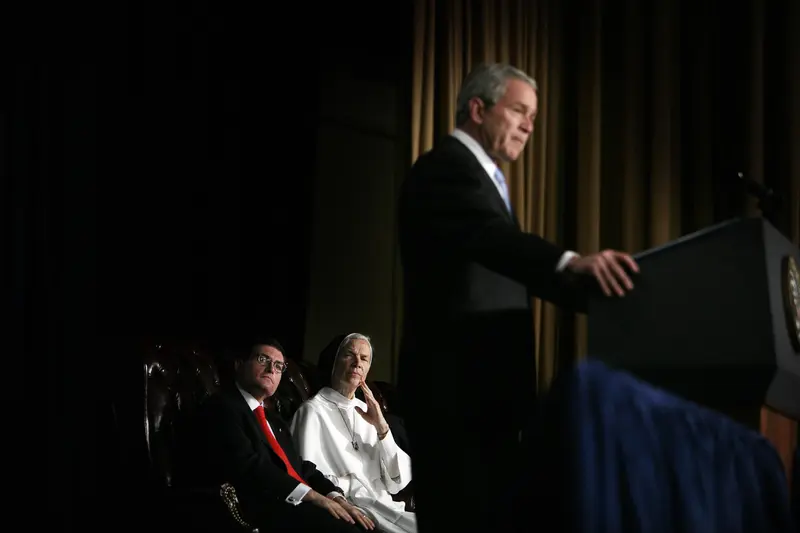

When George W. Bush became president, Leo seized the opportunity to have even greater influence. He recommended lawyers to hire for key administration jobs and was tapped as one of four outside advisers on judicial nominees — a group nicknamed the “four horsemen.” Leo and Brett Kavanaugh, then a young White House lawyer and an active Federalist Society member, teamed up to break a logjam in the Senate blocking Bush’s lower-court nominees. In one email, a White House aide called Leo the point person for “all outside coalition activity regarding judicial nominations.”

In another email chain, previously unreported, a group of Bush Justice Department lawyers discussed how best to publicize a white paper promoting a controversial nominee to an appeals court. One lawyer said he was looking for an organization to “launder and distribute” the paper, presumably so it wouldn’t come from the Bush administration itself. “Use fed soc,” Viet Dinh, a Federalist Society member who was then a high-ranking official at the DOJ, replied. “Tell len leo I need this distributed asap.” (Leo declined to comment on this.)

In 2005, Leo’s bonds with the White House tightened further, when Bush was presented with two U.S. Supreme Court vacancies in rapid succession. On a flight on Air Force Two, Vice President Dick Cheney gave Steve Schmidt, then a White House deputy assistant, two duffel bags full of binders on potential nominees. Schmidt gathered a team to push through the nomination of John Roberts, Bush’s choice to fill the seat of Chief Justice William Rehnquist. The group met in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, a warren of offices next to the White House. At first, Leo was one among the crowd. But he pushed his way up, Schmidt said. “If you take it down to a school committee, like the PTA committee, who’s going to be the chairperson of the committee? It’s going to be the person who cares the most and shows up to all the meetings,” Schmidt said in an interview. “This is what Leonard Leo did.”

Leo worked outside the administration, too. In a sign of his growing sophistication, he formed what would be a key weapon in furthering the conservative takeover of the courts. He and several other lawyers launched the Judicial Confirmation Network, a tax-exempt nonprofit that could spend unlimited sums without publicly revealing its donors. The group did something unusual for that time: It treated a confirmation battle like a political campaign. JCN ran positive ads about Roberts while its spokespeople fed reporters glowing quotes. On paper, the network was independent of the Federalist Society and the White House, but the boundaries were porous. Leo didn’t formally run it, but White House staffers understood that JCN was a Leo group. “Leonard was the guy,” Schmidt said. “A hundred percent.” In his response to questions, Leo confirmed he helped launch the group. (JCN did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Roberts’ confirmation was swiftly followed with yet another Supreme Court opening. Bush at first nominated his counsel, Harriet Miers. Conservatives — Leo’s allies — protested: Her resume was thin, her views on abortion suspect. Bush soon withdrew her nomination and offered a hard-right conservative: Samuel Alito. JCN ran yet more ads.

At a 2006 Federalist Society gala, Leo introduced now-Justice Alito to rapturous applause. He also made light of the group’s growing influence over judicial selection, which had drawn suspicions from Democrats. “It is a pleasure to stand before 1,500 of the most little known and elusive of that secret society or conspiracy we call the Federalist Society,” he said. “You may pick up your subpoenas on the way out.”

One of the first things a visitor sees upon entering the Catholic Information Center in downtown Washington is a painting of a smiling young girl. Jesus Christ stands above her, eyes closed and a hand on her head. The girl is identified as “Margaret of McLean.” Margaret was Leo’s oldest child, who died in 2007 from complications related to spina bifida when she was 14 years old. Leo has said that his faith was deepened by Margaret’s life and death.

The Catholic Information Center is a bookstore, event space and place of worship. Its location in the nation’s capital is no accident: On its website, the center boasts that it is the closest tabernacle to the White House. Leo is a major supporter of the CIC, and its unabashed projection of political power aligns with the central role of religion in Leo’s political project. Standing at the nexus of the conservative legal movement and the religious right, Leo forged a connection with several of the Supreme Court’s conservative justices, who shared a deep Catholic faith and a legal ideology with Leo. Antonin Scalia, Leo has said, became “like an uncle.” Thomas is a godfather to one of Leo’s daughters and keeps a drawing by Margaret in his chambers. Leo has dined and traveled with Alito, displaying in his office a framed photo of himself, Alito and Alito’s wife, Martha-Ann, standing outside the Palace of Versailles.

George Conway saw this courtship firsthand. Before he became one of the most prominent “Never Trumpers,” Conway had been a veteran of the conservative movement. He served on the Federalist Society Board of Visitors, donated to the group and was briefly considered for a top position in the Trump Justice Department. His then-wife, Kellyanne Conway, was a prominent pollster who later managed Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign.

From his rarefied position, Conway watched Leo become what he called a “den mother” to the justices. In liberal Washington, conservatives — even the most powerful ones — believed themselves to be misunderstood and unfairly maligned. Leo saw it as his responsibility, Conway said, to help take care of the judges even after they had made it to the highest court in the country. “There was always a concern that Scalia or Thomas would say, ‘Fuck it,’ and quit the job and go make way more money at Jones Day or somewhere else,” Conway said, referring to the powerful conservative law firm. “Part of what Leonard does is he tries to keep them happy so they stay on the job.”

“There was always a concern that Scalia or Thomas would say, ‘Fuck it,’ and quit the job and go make way more money at Jones Day or somewhere else.”

On the sidelines of the Federalist Society’s annual conference, Leo made a habit of hosting a dinner at a fancy restaurant where he invited one or two justices or prominent political or legal figures (Scott Pruitt, the Oklahoma attorney general who would later serve in Trump’s cabinet, was one guest) and major donors. “With Leonard, it went both ways,” Conway said. “It made the justices happy to meet people who revered them. It made the donors happy to meet the justices and no doubt more inclined to give to Leonard’s causes.”

In 2008, as ProPublica first reported, he helped organize a weekend of salmon fishing in Alaska that included Alito and Paul Singer, the hedge fund billionaire and Leo donor. Leo invited Singer on the trip, according to ProPublica’s reporting, and Leo also asked Singer if he and Alito could fly on Singer’s plane. The Alaskan fishing lodge where the three men stayed was owned by Robin Arkley II, a California businessman and also a Leo donor. (Alito has written that the trip did not require disclosure.)

Leo has helped arrange for Scalia and Thomas to attend private donor retreats hosted by the Koch brothers dating as far back as 2007; once, Leo even interviewed Thomas at a Koch summit. The Federalist Society flew Scalia to picturesque locales like Montana and Napa Valley to speak to members. After his Napa appearance, Scalia flew to Alaska for a fishing trip on a plane owned by Arkley. Both Singer and Arkley were generous and early donors to JCN. (Arkley said in a statement: “Nothing has been more consequential in transforming the courts and building a more impactful conservative movement than the network of talented individuals and groups fostered by Leonard Leo.” Singer did not comment.)

Leo came to the aid of Thomas’ wife, Ginni, when she launched her own consulting firm, and he directed Kellyanne Conway in 2012 to pay her at least $25,000 as a subcontractor, according to The Washington Post. “No mention of Ginni, of course,” Leo instructed Conway. Leo denied that the payments had any connection to the Supreme Court’s work, and he said he obscured Ginni Thomas’ role to “protect the privacy of Justice Thomas and Ginni.”

Leo was not the only person who used faith and ideology as a bridge to the justices. Reverend Rob Schenck is a longtime evangelical Protestant minister who spent decades as a leader in the religious right. Schenck didn’t work directly with Leo, but he said he too befriended several justices, praying with them in their chambers and socializing with them outside of the court. He came to recognize the justices’ “feet of clay,” their human appetites and frailties.

“I know how much it benefited me to say to donors, ‘I was with Justice Scalia last night or last week’” or that I “‘had a lovely visit with Justice Thomas in chambers,’” Schenck said in an interview. “Anybody can try to get change at the Supreme Court by filing an amicus brief — almost anybody, let’s put it that way. But how many people can get into chambers, or better yet into a justice’s home?”

In 2007, Leo gave the young Republican governor of Missouri, Matt Blunt, a career-defining test. A vacancy had opened up on the state Supreme Court. Missouri has had a nonpartisan process for picking new justices, in which a panel of lawyers and political appointees select candidates for the governor to choose. Known as the Missouri Plan, it had been adopted in some way by dozens of states. Blunt, the scion of a Missouri dynasty, was likely to uphold that tradition as his state’s governors had for the last 60 years. But Leo pressed him to jettison it. Leo did not do this politely.

That year, with the Alito and Roberts confirmations in hand, the Federalist Society was turning its attention to the state courts, devoting nearly a fifth of its budget to the initiative. Leo traveled the country, delivering a stump speech of sorts. His early target, in ways that have not been previously reported or understood, was Missouri.

He and his allies did not like the state’s system. To conservatives, the plan’s nonpartisan structure was a cover for allowing the left-leaning bar to pack the bench with centrist or left-wing justices. Leo’s allies preferred, according to interviews, that the power to select judges be put in the hands of the executive or given to voters at the ballot box. “If you could beat the Missouri Plan in Missouri, you could tell the rest of the states, ‘There is no more Missouri Plan,’” the former chief justice of Missouri’s supreme court, Michael Wolff, said in an interview. “It was a big deal.”

To achieve that, Leo worked a back channel directly to Blunt. The outlines of Leo’s campaign are contained in the paper records of an old whistleblower lawsuit and in emails obtained by The Associated Press as part of a 2008 legal settlement with the Missouri governor’s office. These records show Leo lobbying Blunt’s chief of staff, Ed Martin, and sometimes Blunt himself.

With the Alito and Roberts confirmations in hand, the Federalist Society was turning its attention to the state courts, devoting nearly a fifth of its budget to the initiative.

In the summer of 2007, the judicial panel offered Blunt three finalists. Two were Democrats. The third was Patricia Breckenridge, a centrist Republican. When her name appeared, Leo and his team mobilized, collecting negative research on Breckenridge and lobbying the governor. “I was shocked to see the slate tendered by the Commission the other day,” Leo wrote in an email to Blunt. “It would be very appropriate for you to scrutinize the candidates, and if they fail to pass those tests, to return the names.”

“Return the names” sounded anodyne; it was not. Leo and other Federalist Society leaders had a strategy: They wanted to tarnish Breckenridge’s reputation, spike her candidacy and then use the ensuing disarray to pry Missouri away from its long-standing way of picking justices. Blunt found the character attacks distasteful and worried that if he rejected Breckenridge, the panel would pick one of the Democrats, according to a person familiar with his thinking. Leo wasn’t having it. “He will have zero juice on the national scene if he ends up picking a judge who is a disgrace,” Leo wrote to Martin, the chief of staff. “If this happens, there will be fury from the conservative base, the likes of which you and the Governor have never seen.”

Blunt appointed Breckenridge anyway. Leo piled on. “Your boss is a coward and conservatives have neither the time nor the patience for the likes of him,” he wrote to Martin.

The person familiar with Blunt’s thinking said the governor did not feel threatened. But a few months later, Blunt, surprising nearly everyone, said he wasn’t running for reelection. He had, he said, accomplished all he wanted. At 37 years old, his political career was over.

For four more years, Leo’s team continued to target the Missouri Plan in Missouri. The Judicial Confirmation Network, now rebranded as the Judicial Crisis Network, gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to the effort. It failed again. But Leo, JCN and the Federalist Society took the lessons they learned in Missouri and applied them elsewhere, with profound implications for democracy.

As Leo continued to work his influence with state judicial appointments, he also homed in on what proved to be a softer target: states that elected their top judges. Judicial elections were low-information races, where money could make a difference. After a decade and a half, he achieved what he had not in Missouri: more partisan courts, with hard-line conservatives having a shot and many taking their places on the bench.

Leo became interested in Wisconsin in 2008. An incumbent state Supreme Court justice, Louis Butler, had angered the state’s largest business group with his ruling in a lead paint case. The ensuing ad campaign was contentious and expensive, featuring commercials showing Butler, who is Black, next to the picture of a sex offender who was also Black. To have those two pictures “right next to each other, one sex offender, one a justice on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, took our breath away,” Janine Geske, a former justice on the court, said in an interview. (She was initially appointed by a Republican governor to fill a vacancy.) “Most of us were looking at that, thinking, what have we descended to in terms of ads?”

Behind the scenes, Leo himself raised money for Butler’s challenger, Michael Gableman, according to a person familiar with the campaign. Leo passed along a list of wealthy donors with the instructions to “tell them Leonard told you to call,” this person said. Each donor gave the maximum. Gableman won the race, the first time a challenger had unseated an incumbent in Wisconsin in 40 years. Leo declined to comment on his role.

The push for loyal conservatives intensified after the 2010 election cycle. Republicans took over many state houses and legislatures. But they realized they could sweep to power, yet judges could overrule their initiatives. Republicans counted on Leo for $200,000 to elect a judge who would back Republican Gov. Scott Walker, who was then embroiled in a recall campaign, according to emails. That judge won. Walker stayed in power.

In 2016, Walker had a vacancy to fill, and it was a plum one: The new justice would fill out three and a half years before having to run for the seat. Walker had three people on his shortlist: two court of appeals judges and Dan Kelly. Kelly had been an attorney for an anti-abortion group and was the Milwaukee lawyers chapter head of the Federalist Society, but he had never been a judge.

“Leo stepped in and said it’s going to be Dan Kelly,” a person familiar with the selection said. “There is zero question in my mind, the Federalist Society put the hammer down.” When asked about this, Leo wrote, “I don’t remember,” adding, “I have known Dan Kelly for a number of years.” Walker said he had not discussed the race with Leo. Kelly did not respond to requests for comment.

Over the next several years, Leo, through the Judicial Crisis Network, continued to back conservative candidates in Wisconsin, where judicial elections are, putatively, nonpartisan. In one 2019 race, JCN funneled over a million dollars into the contest in its final week; the Republican narrowly won. But money can’t always deliver in politics. In the complicated political year of 2020, Kelly, even with the backing of Leo and Trump, lost the race to hold on to his seat.

He ran again in 2023. By this time, the Democrats had caught on and the arms race was joined. Democrats, activated by the Dobbs decision and a gerrymander that had left Republicans with a dominant position in the state Legislature, ponied up with big money.

At least $51 million was spent, including millions from groups associated with Leo. He personally donated $20,000, the maximum allowable, to the Kelly campaign. This was after Kelly aligned himself with those rejecting the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

The most expensive state Supreme Court race in U.S. history ended the night of April 4, 2023. The candidate the Democratic Party supported, Janet Protasiewicz, won handily, giving the liberals control of the state court for the first time in years. Kelly conceded on a bitter note. “It brings me no joy to say this,” he told the affirming crowd. “I wish in a circumstance like this I would be able to concede to a worthy opponent. But I do not have a worthy opponent to which to concede.”

Kelly’s loss was Leo’s loss. But it was also, paradoxically, a win. Conservatives were acting as if judgeships were a prize for a political party, rather than an independent branch of government — what Geske calls “super-legislators.” And thanks to Leo, those super-legislators could be especially hard-line.

Conservatives were acting as if judgeships were a prize for a political party, rather than an independent branch of government: "super-legislators."

In North Carolina, Leo and his allies found another lab for their strategy.

In 2012, JCN began spending in North Carolina, part of an infusion of funds that toppled Judge Sam Ervin IV, the grandson of the Watergate prosecutor. “All of a sudden we started seeing what I would consider misleading and distortive” political ads, Robert Orr, a former Republican state Supreme Court justice in North Carolina, said in an interview. “We’d never seen those in judicial races.” Democrats were able to resist the onslaught for several years, maintaining control of the high court. But conservative outside groups consistently outspent their Democratic-leaning counterparts, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan legal institute. The Republican State Leadership Committee, or RSLC, a group focused on state elections, outspent all the other groups. JCN has been a top donor to the group.

By 2021, tax returns show, virtually all of JCN’s budget came from the Marble Freedom Trust, for which Leo is trustee and chairman. JCN and RSLC did not respond to requests for comment.

In 2022, a year generally unfavorable to Republicans, the RSLC claimed credit for flipping North Carolina’s top court to a 5-2 Republican majority. Almost as soon as it was seated, the freshly Republican-dominated court did something extraordinary. In March 2023, the court reheard two voting rights cases its predecessor had just decided. The first was over gerrymandered districts that heavily favored Republicans. The second was over a voter identification law the previous court had found discriminated against Black people.

Nine months earlier, Justice Phil Berger Jr., son of the state Senate president, had attended the party at Leo’s home, in Northeast Harbor, Maine, as conservatives basked in the triumph of their movement.

Now, the newly elected conservative majority delivered victories for Republicans in the two cases. The voter ID decision was authored by Berger.

In 2013, Mike Black, Leo’s former classmate at Cornell Law, was leading the civil division of the Montana attorney general’s office as a career employee. A new attorney general had just been elected, bringing with him a number of new staffers to the office. Black had a matter to discuss with one of them: a tall, rangy Harvard Law School graduate named Lawrence VanDyke. VanDyke had been hired as solicitor general, the top appellate litigator in the attorney general’s office, responsible for defending state laws.

Standing in VanDyke’s office, Black noticed several bobblehead dolls on a shelf. “There was like Scalia for sure. And I think probably Alito, there were like four or five. And then there was this one younger-looking guy, and I said, ‘Well, who the heck is this?’” Black recalled. “And he goes, ‘Well, that’s Leonard Leo.’”

Black was astonished.

What Black did not know was by that time that Leo had helped to cultivate an entire generation of conservative lawyers on the rise. The system was like a positive feedback loop: Young attorneys could accelerate their own careers by affiliating with the Federalist Society and then prove their worth by advancing bold, conservative doctrines in the courts. Leo himself would suggest candidates to state attorneys general. According to one former Republican attorney general: “He won’t say, ‘Hire this person,’ in a bossy way. He’ll say: ‘This is a good guy. You should check him out.’”

In 2014, the Republican Attorneys General Association, a campaign group, became a standalone organization. The first 17 contributions were each for $350 apiece. Then came a donation of a quarter of a million dollars. It came from JCN. Rebranded as The Concord Fund, the group remains RAGA’s biggest and most reliable funder today. (In response to questions for this story, RAGA’s executive director said “Leonard Leo has done more to advance conservative causes than any single person in the history of the country.”)

Attorneys general are more likely than private plaintiffs to have the ability, or standing, to bring the types of high-impact cases prioritized by Leo and his network. After the federal government itself, state attorneys general collectively are the second-largest plaintiff in the Supreme Court.

“Leonard Leo has done more to advance conservative causes than any single person in the history of the country.”

VanDyke had been a Federalist Society member since his time at Harvard Law. He was an editor of the conservative Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. He worked at a major firm in Washington under Gene Scalia, the Supreme Court justice’s son, before becoming assistant solicitor general in Texas.

Despite his skill and credentials, VanDyke quickly alienated colleagues in the Montana attorney general’s office. Black said VanDyke had little appetite for the bread-and-butter state court cases that came with the job. Instead, emails show, VanDyke was excited by hot-button issues, often happening out of state. For example, he recommended Montana join a challenge to New York’s restrictive gun laws, passed after the Sandy Hook school massacre, adding as an aside in an email, “plus semi-auto firearms are fun to hunt elk with, as the attached picture attests :)” VanDyke persuaded Montana to join an amicus in the Hobby Lobby case, which led to the Supreme Court recognizing for the first time a private company as having religious rights.

For many years, solicitor general was considered a slow-metabolism job. VanDyke, who declined to comment, represented a new generation who had a distinctly aggressive, national approach to the law. Just recently, state solicitors obtained an injunction blocking federal agencies from working with social media companies to fight disinformation, persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to undo the Biden administration’s student debt relief plan and limited the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate greenhouse gasses. Dobbs, the ruling that ended women’s right to an abortion, was argued by Mississippi’s solicitor general.

For VanDyke, state solicitor general was a stepping stone on the judiciary path, especially with Leo’s hand at his back. In 2014, he quit the Montana attorney general’s office to run for state Supreme Court, in what turned out to be a bitter contest inflamed by record independent expenditures. The Republican State Leadership Committee, which received funding from JCN, spent more than $400,000 to support VanDyke. He lost. After that, Leo made at least one call on VanDyke’s behalf to an official who might be in a position to give him a job, a person with knowledge of the situation said. This was not an uncommon move.

Leo said he did not recall making calls on VanDyke’s behalf. He acknowledged nurturing the careers of a whole generation of young conservative attorneys, among them VanDyke; Andrew Ferguson, the Virginia solicitor general; Kathryn Mizelle, the federal judge who struck down the federal mask mandate for air travel; and Aileen Cannon, the federal judge overseeing the Trump Mar-a-Lago documents case.

After Montana, VanDyke landed in Nevada as solicitor general under Adam Laxalt, an ally of Leo’s. In the Trump administration, VanDyke worked briefly for the Justice Department before the president nominated him to be a judge on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Less than a year later, Trump released a fourth list of potential Supreme Court nominees. More than a third of the names were alumni of state attorney general offices.

The final name on the list: Lawrence VanDyke.

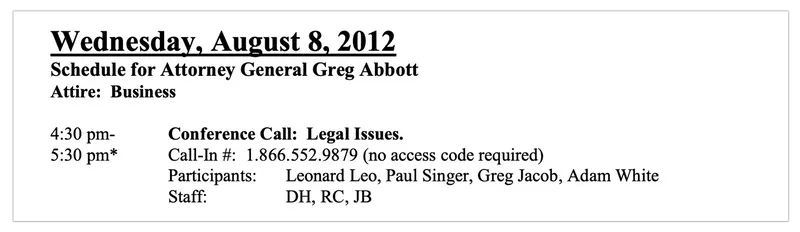

In August 2012, the attorney general of Texas, Greg Abbott, had a conference call scheduled with Leo. It was Leo’s third calendar meeting with Abbott that year, records show. (Abbott is now the governor.) This meeting included not only Abbott and Leo, but also Paul Singer, the hedge fund manager who had been on the Alaska fishing trip. Two attorneys representing a small Texas bank, which had sued the Obama administration over its rewrite of banking laws, were invited. The meeting, which hasn’t previously been reported, highlights another key lever in Leo’s machine: The ability to bring donors’ policy priorities to public servants who can do something about those priorities.

After the 2008 financial crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank regulatory overhaul, aimed at preventing another meltdown. Singer became one of the law’s biggest critics. In op-eds and in speeches, he argued that the new banking rules were unworkable and that efforts to prevent banks from becoming too big to fail could in fact make the system more fragile. Singer was especially critical of a provision known as “orderly liquidation authority,” which allows regulators to quickly wind down troubled institutions, calling it “entirely nutty.”

Leo took up the cause. According to interviews and meeting details obtained by the liberal watchdog group Accountable.US, Leo spoke with attorneys general in at least three states about a legal challenge to Dodd-Frank. He scheduled conference calls with the Oklahoma and Texas attorneys general at the time, Scott Pruitt and Abbott, respectively, to talk about what they could do about Dodd-Frank.

Oklahoma and Texas joined the bank’s case as co-plaintiffs. Montana joined, too. A person who worked in the Montana attorney general’s office said Leo called its newly elected leader, Republican Tim Fox, about the case. Montana would not have joined the suit, this person said, if Leo had not called Fox. VanDyke, then Montana’s solicitor general, became an attorney of record on the case.

Singer, Fox, Abbott and VanDyke did not comment for this story. Leo told ProPublica he didn’t recall a meeting with Abbott and Singer, and didn’t remember placing a call to Fox. He said he supported a legal challenge to the Dodd-Frank law on the grounds that its creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is unconstitutional.

In total, 11 states signed on. When they joined, the suit was amended to specifically challenge orderly liquidation authority as unconstitutional — the provision that Singer had singled out for criticism. For two years, the suit advanced through the courts, landing in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2015. After an adverse ruling there, the attorneys general dropped out.

There had been doubters. A high-ranking attorney in the Texas attorney general’s office thought the suit was likely to fail. One former Republican attorney general from a different state said he didn’t believe the suit was critical to his state’s interests.

Leo’s network made an example of one. After Greg Zoeller, Indiana’s Republican attorney general, did not sign on, The Washington Times ran an opinion piece by JCN’s policy counsel — himself a former assistant attorney general in Missouri — speculating that Indiana’s attorney general may have been motivated by “strong alliances with Wall Street banks.” After two terms, Zoeller chose not to run for reelection in 2016, saying before he left office, “I don’t know if I fit today’s political arena.”

On a chilly day in March 2017, about six weeks into Trump’s presidency, Leo arranged for a select group to have a private audience with Justice Clarence Thomas at the U.S. Supreme Court. The attendees were a group of high-net-worth donors who had been organized by Singer to marshal huge resources toward electing Republicans and pushing conservative causes. That afternoon, the donors spoke with Thomas. The previously unreported meeting was described by a person familiar with it and corroborated by planning documents.

The donors left the meeting on a high and walked a short distance to the soaring Jefferson building of the Library of Congress. Singer’s group, the American Opportunity Alliance, was holding a gala dinner for 75 people, where they would hear from “scholars, university leaders and academics bringing unique insights on the issue of free speech,” according to planning documents obtained by ProPublica. Leo told ProPublica that while not all of the alliance’s donors give money to his causes: “They are thought leaders who should know more about the Constitution and the rule of law. I was happy to arrange for them to hear about these topics from one of the best teachers on that I know, Clarence Thomas.” Singer declined to comment. The Supreme Court didn’t respond to a request for comment.

A year and a half later, when Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court was teetering, Leo turned to Alliance donors to raise emergency funds for advertisements that would counter the relentless stream of negative press. He told donors that he needed to raise $10 million as fast as possible, according to a person familiar with the call. Swiftly, JCN was on the airwaves defending Kavanaugh. Leo called Mike Davis, the top aide on nominations for Senate Republicans, and urged him to press ahead, emails show. (Leo declined to comment on this.)

“We’re going to have great judges, conservative, all picked by the Federalist Society.”

Leo had been in a state of high mobilization since Scalia’s death in February 2016 while Barack Obama was still president. “Staring at that vacancy,” Leo later said, “fear permeated every day.” In late March, with Trump’s nomination all but wrapped up, Leo, Trump and his campaign lawyer Don McGahn met at the offices of the law firm Jones Day. Trump emerged with a list of potential nominees to the U.S. Supreme Court and then advertised it: “We’re going to have great judges, conservative, all picked by the Federalist Society,” he said.

With Scalia’s vacancy and two more justices approaching the end of their careers, Leo embraced a more public position. “He makes a calculation to kind of come out from the shadows and put himself front and center, because he knows that that will give Republican voters confidence to vote for Donald Trump in the 2016 election,” Amanda Hollis-Brusky, a Pomona College professor and author of “Ideas With Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution,” said in an interview. “But that’s sort of an Icarus moment too, where they’re getting really close to the sun.”

Once Trump took office, he gave control over judicial picks to Leo, McGahn and other conservative lawyers with strong connections to the Federalist Society. With Leo’s help, Trump appointed 231 judges to the bench in his four years. Of the judges Trump appointed to the circuit courts and the Supreme Court, 86% were former or current Federalist Society members.

The Federalist Society’s alliance with Trump appalled some of its prominent members. Andrew Redleaf, a longtime donor and adviser to the group who has known its co-founders since college, viewed Leo’s work for Trump as “an existential threat to the organization,” he said in an interview. Redleaf and his wife, Lynne, offered to donate $100,000 to pay for a crisis communications firm that could distance the group from Leo and his work for Trump. Federalist Society President Gene Meyer was “genuinely sympathetic” to his position, Redleaf said, but declined the money and advice. Meyer did not respond to requests for comment.

Leo said in a statement: “The Federalist Society today is larger, more well-funded, and more relied upon by the media and thought leaders than ever before. So much for Mr. Redleaf’s ‘existential threat.’”

In early 2020, Leo told the news site Axios he planned to leave his day-to-day role at the Federalist Society after nearly 30 years, though he would remain on the board. Soon, Leo received all the money he would ever need to fuel his next efforts. For more than a decade, he had cultivated a relationship with a businessman named Barre Seid, who ran and owned the Chicago electronics manufacturer Tripp Lite.

Seid, who is Jewish, had long donated to conservative and libertarian causes, from George Mason University to the climate-skeptic group the Heartland Institute. Seid decided to put Leo in charge of his fortune — $1.6 billion, what was then the largest known political donation in the country’s history. Through a series of complicated transactions, Seid transferred ownership of his company to a newly created entity called Marble Freedom Trust, of which Leo was the sole trustee. (Seid did not respond to requests seeking comment.)

In late 2021, Leo took over as chairman of a “private and confidential” group called the Teneo Network. In a promotional video for the group, Leo sits on a couch in a charcoal jacket, no tie. Over upbeat music, Leo says: “I spent close to 30 years, if not more, helping to build the conservative legal movement. At some point or another, I just said to myself, ‘Well, if this can work for law, why can’t it work for lots of other areas of American culture and American life where things are really messed up right now?’” Leo went on to say his goal was to “roll back” or “crush liberal dominance.” The group had long quietly gathered conservative capitalists and media figures with politicians like Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley. Under Leo’s watch its budget soared, and new members have joined from all the corners of Leo’s network: federal and state judges, state solicitors general, a state attorney general and the leaders of RAGA and RSLC.

Other of Leo’s ventures show a willingness to embrace increasingly extreme ideas that could have sweeping consequences for American democracy. The Honest Elections Project, a direct offshoot of a group in Leo’s network, focused on election law and voting issues, was a major proponent of a legal concept known as independent state legislature theory. That theory claimed that, under the Constitution, state legislatures had the sole authority to decide the rules and outcomes of federal elections, taking the role of courts out of the equation entirely. If the theory prevailed, experts said, it could have given partisan state legislators the power to not only draw gerrymandered maps but potentially subvert the result of the next presidential election.

The Honest Elections Project filed an amicus brief when a case about the theory reached the Supreme Court. (The Supreme Court ultimately ruled against an expansive reading of the theory but did not entirely rule it out in the future.) Leo defended the Honest Elections Project, saying that “in all of its programming” it “seeks to make it easy to vote and hard to cheat. That’s a laudable goal.”

Leo’s own rhetoric has grown more extreme. Late last year, he accepted an award from the Catholic Information Center previously given out to Scalia and Princeton scholar Robert George. Rather than strike a celebratory tone, he reminded his audience of Catholicism’s darkest days in history starting with the Siege of Vienna by the Ottomans in the 17th century. Today, he continued, Catholicism remained under threat from what he called “vile and immoral current-day barbarians, secularists and bigots” who he calls “the progressive Ku Klux Klan.” These opponents, he said, “are not just uninformed or unchurched. They are often deeply wounded people whom the devil can easily take advantage of.” And after Dobbs, these barbarians were “conducting a coordinated and large-scale campaign to drive us from the communities they want to dominate.”

It wasn’t long before the backlash to Dobbs, and to Leo’s role in that decision, arrived on his doorstep. In 2020, Leo and his family moved to Northeast Harbor, a wealthy enclave on the Maine coast. The Leo family had spent time each summer there for almost two decades. In 2019 they bought a $3 million mansion, Edge Cove, from an heir of W.R. Grace, founder of the chemicals corporation.

Leo told The Washington Post that Edge Cove — which underwent more than a million dollars’ worth of renovations — would serve as “a retreat for our large family and for extending hospitality to our community of personal and professional friends and co-workers.” The Leo family eventually started living there most of the year.

But Northeast Harbor has not proven to be the quiet retreat that Leo hoped it would be. In 2019, Leo hosted a fundraiser at the Maine house for Republican Sen. Susan Collins. Collins had cast the deciding vote in favor of Kavanaugh’s nomination, and the news of the fundraiser sparked protests by local residents and liberal activists in the area. After the Dobbs decision, locals say, Leo’s presence became an ongoing flashpoint and a source of drama in a town unaccustomed to such things.

On the evening of the Dobbs decision, protesters held a vigil outside Leo’s house, which was followed by frequent protests. One resident planted a sign in her yard that urged passersby to “Google Leonard Leo.” Another wrote messages like “LEONARD LEO = CORRUPT COURT” in chalk in the street outside Leo’s house.

Bettina Richards runs a record company in Chicago and spends the summers in Northeast Harbor. She lives just down the road from Leo. She didn’t know much about Leo until the Dobbs decision, but afterward, she said protestors got permission from a neighbor of Leo’s to hang a pink fist flag across from his house. Leo displayed several different flags with Catholic iconography outside his house.

One day Richards got a call that Leo’s security guard had walked onto private property to tear the fist flag down. Richards biked over to repair it. Leo approached with his guard, and Richards told them not to touch it. “I will allow it,” Leo replied, according to Richards. (Leo said in his written statement: “The owner of that property came to us some weeks later stating that whoever put the flag up did not have permission and that the property owner would be taking it down.” Richards said another household member had OK’d the flag.)

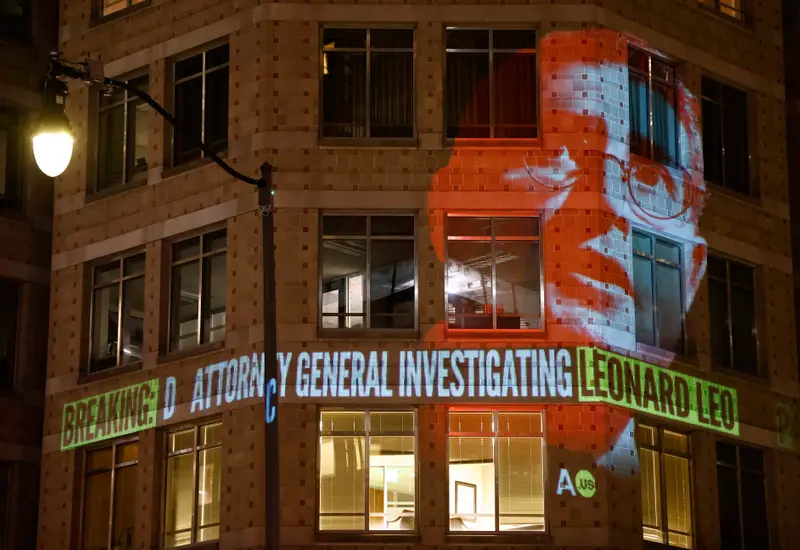

As Leo enters his fifth decade of activism, he has become too big to ignore. Liberal opposition research groups with their own anonymous donors have launched campaigns to expose his influence and his funders; one group even projected an image of Leo’s face onto the building that houses the Federalist Society’s headquarters in Washington. In August, Politico reported that the District of Columbia’s attorney general was investigating Leo for possibly enriching himself through his network of tax-exempt nonprofit groups. A lawyer for Leo has denied any wrongdoing and said Leo will not cooperate with the probe. In response to ProPublica’s reporting about Leo’s role in connecting donors with Supreme Court justices, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Durbin, D-Ill., and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., demanded information from Leo, Paul Singer and Rob Arkley about gifts and travel provided to justices. A lawyer for Leo responded that he would not cooperate, writing that “this targeted inquiry is motivated primarily, if not entirely, by a dislike for Mr. Leo’s expressive activities.”

Through it all, Leo has remained defiant. His vision goes beyond a judiciary stocked with Federalist Society conservatives. It is of a country guided by higher principles. “That’s not theocracy,” he recently told a conservative Christian website. “That’s just natural law. That’s just the natural order of things. It’s how we and the world are wired.”